Chicheley Hall

| Chicheley Hall | |

|---|---|

"the brick[work] is among the finest of any house of this date" | |

| Type | House |

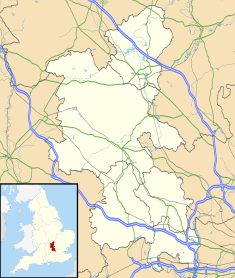

| Location | Chicheley, Buckinghamshire |

| Coordinates | 52°06′13″N 0°40′45″W / 52.1036°N 0.6792°W |

| Built | 1719-1721 |

| Architect | Francis Smith |

| Architectural style(s) | Baroque |

| Governing body | Royal Society |

| Owner | Sir John Chester Bt |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Chicheley Hall |

| Designated | 3 March 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1212277 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Stable block SW of Chicheley Hall |

| Designated | 3 March 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1212279 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Service Wing with attached quadrant link NW of Chicheley Hall |

| Designated | 9 March 1982 |

| Reference no. | 1289598 |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Dovecote S of Chicheley Hall |

| Designated | 3 March 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1212329 |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Garden House NW of Chicheley Hall |

| Designated | 16 February 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1212332 |

Chicheley Hall, Chicheley, Buckinghamshire, England is a country house built in the first quarter of the 18th century. The client was Sir John Chester, the main architect was Francis Smith of Warwick and the architectural style is Baroque. Later owners included David Beatty, 2nd Earl Beatty and the Royal Society. Chicheley Hall is a Grade I listed building.

History

[edit]Earlier buildings

[edit]A manor house on the site belonged to the Pagnell family of Newport Pagnell, but was donated by them to the church. Cardinal Wolsey gave the manor to Christ Church, Oxford, but it subsequently reverted to the Crown after Wolsey's fall and was acquired by a wool merchant, Anthony Cave, in 1545, who built a manor house in the form of a hollow square.[1] On his death the house was left to his daughter Judith, who had married her cousin William Chester, son of Sir William Chester. Their only son Anthony was High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire for 1602 and created a baronet in 1620.[2]

The house then descended in the Chester family to the time of the English Civil War, when it was shelled by Parliamentary forces and eventually demolished. The present Chicheley Hall was built in the early 1700s on the same site. All that remains of the old manor house is one Jacobean over-mantel with termini caryatids, and some panelling in the new Chicheley Hall.[3]

Building the current hall: 1719-1724

[edit]The present hall was built between 1719 and 1723,[a] with the interior fittings completed in 1725.[6] The house was often attributed to the architect Thomas Archer,[4] but more recent research suggests Francis Smith,[3] who is thought to have designed it for Sir John Chester, 4th Baronet.[b][7]

After John Chester's death the house descended to Charles Bagot Chester, the 7th Baronet, a drunk and gambler, who jumped out of a second floor window in a drunken fit. Before dying of his injuries he bequeathed all of his estates, including Chicheley, to a distant relative and school friend, Charles Bagot, on condition he adopted the name of Chester. Charles' son Charles Bagot Chester, a gambler, rake and Member of Parliament, rented out the hall for many years. After his death the estate descended to the unmarried Charles Anthony Chester and from 1883 was again rented out to a series of tenants for the next 70 years.[8]

20th century

[edit]In 1911, the Hall was rented by Sir George Farrar, a Randlord who made his fortune in gold in South Africa, and his wife Ella. Their daughter Gwen was a noted cellist.[9]

During the Second World War, Chicheley Hall was used by the Special Operations Executive as its Special Training School No. 46. From 1942 until 1943, it was used for training Czechoslovaks for SOE parachute missions.[10][11] The hall was later used as a base to train Polish agents, and then became a FANY wireless telegraphy school.[12] Fortunately, the fine interior was protected by hardboard.

The house was purchased from the Chester family in 1952 by David Beatty, 2nd Earl Beatty.[13] Beatty, son of Admiral Lord Beatty, began a large restoration programme and finally employed the renowned interior decorator Felix Harboard, famed for his work at Luttrellstown Castle near Dublin.[13] Harboard's classical colour schemes accentuating moulding and panelling perfectly suit the house. Chicheley Hall remained the home of the 2nd Earl's fourth wife, Diane, after his death. She remarried, to Sir John Nutting, and was later the chairman of the Georgian Group. Together, they ran the house as a venue for weddings and conferences, and as a filming location. The house represented Bletchley Park in the 2001 film Enigma.[14]

21st century

[edit]In 2007, Chicheley Hall was offered for sale, with a guide price of £9 million.[15] It was bought by the Royal Society for £6.5 million, funded in part by the Norwegian philanthropist Fred Kavli. The Royal Society spent £12 million renovating the house, and adapting it to become the Kavli Royal Society International Centre, a venue for science seminars and conferences. Outside of these scientific events the hall may be hired for corporate and social events.[16]

Chicheley Hall was operated by De Vere Venues until June 2020, when it closed 'permanently' following (initially) a temporary closure due to the Covid-19 pandemic.[17] Later that year, it was again listed for sale. Writing in Country Life, Penny Churchill noted that the Royal Society had restored the mansion and converted the stable block to a hotel with 48 bedrooms and a conference centre.[18] The hall was sold in March 2021 to Pyrrho Investments.[19]

Architecture and description

[edit]The principal, south, facade of the house is of nine bays and three storeys above a raised basement; the central section of three bays projects.[4] Massive fluted Corinthian pilasters flank the central three bays. These are repeated at each termination of the facade and again divide the second from the third bay of each wing that flanks the central projection. The facade is symmetrical, however the curve-topped windows of the central projection are taller than the flat-topped windows of the wings, thus uniformity at roof level is achieved by an upward curve to the central section from the wings. These motifs, examples of baroque architecture are exceedingly rare in Britain, where baroque was fashionable for a very brief period at the end of the 17th century and beginning of the 18th. The brickwork, from bricks made on site, is described by Nikolaus Pevsner and Elizabeth Williamson, in their 2003 Buckinghamshire volume of the Pevsner Buildings of England, as "among the finest of any house of this date".[4]

The main door opens to a fine panelled Great Hall, in the manner of William Kent with a classical double-height ceiling depicting Herse and her sisters sacrificing to Flora.[4] Through an arcade of marble columns, oak staircases lead to the upper floors.[5] The most remarkable room is the library on the upper floor, with all shelving and books concealed behind what appears to be panelling, thus disguising the room's true use.[3]

The house is surrounded by a park of 100 acres (0.40 km2), including a lake, canal, and 25 acres (100,000 m2) of gardens, laid out by George London and Henry Wise.[13] An avenue of lime trees leads to the house, past an octagonal dovecote. The River Ouse lies to the east.

Listing designations

[edit]Chicheley Hall is a Grade I listed building.[5] The stable block,[20] the service wing,[21] and the dovecote are listed Grade II*.[22] A garden house to the north-west of the hall,[23] and a summerhouse to the north-east are listed Grade II,[24] as are three sets of gates, with attached walls and gate piers.[25] [26][27]

Gallery

[edit]-

The North front

-

The East front

-

The West front

-

The entrance hall

-

A bell board from the time of the 2nd Earl Beatty

Notes

[edit]- ^ Dates vary as to the actual construction period for the hall. Pevsner gives the years 1719-1724[4] while Historic England's listing record suggests 1719-1721.[5]

- ^ The attribution to Thomas Archer was made by Gervase Jackson-Stops. Pevsner suggests that Archer may have been involved in the design but attributes the construction to Francis Smith.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ "Chicheley Hall". WWII Intelligence Activity around Milton Keynes. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "The Story of Chicheley Hall". Royal Society. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 2003, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f Pevsner & Williamson 2003, pp. 245–248.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Chicheley Hall (Grade I) (1212277)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ^ "Chicheley Hall". Chicheley Hall. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ Marcus Binney (8 June 2007). "The finest country house on the market". Times Online. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- ^ Tipping 1908, p. 360.

- ^ "Gwen Farrar". MK Heritage. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ "Czechs in Exile – Addington House". The Czechoslovak Government in Exile Research Society. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ Rees 2005, p. ?.

- ^ "S.O.E - Training of the S.O.E". clutch.open.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c Binney 2007, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Enigma:Chicheley Hall". Waymaking.com. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ "Chicheley Hall". Country Life. 21 June 2007.

- ^ Binney, Marcus (29 March 2009). "Royal Society snaps up a stately hothouse". The Times.[dead link]

- ^ "Milton Keynes wedding venue 'to close permanently' due to impact from coronavirus lockdown". MK fm. 19 June 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Penny (12 November 2020). "The 'architectural jewel' in Buckinghamshire with 'an interior as sumptuous as its exterior'". Country Life.

- ^ Price, Katherine (7 March 2021). "Chicheley Hall sold for £7m to Pyrrho Investments". The Caterer.

- ^ Historic England. "Stable block SW of Chicheley Hall (Grade II*) (1212279)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Service Wing with attached quadrant link NW of Chicheley Hall (Grade II*) (1289598)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Dovecote S of Chicheley Hall (Grade II*) (1212329)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Garden House NW of Chicheley Hall (Grade II) (1212332)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Summerhouse NE of Chicheley Hall (Grade I) (1212277)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Wall with Attached Stone Pier and Pair of Gate Piers N of Chicheley Hall (Grade II) (1212333)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Gatepiers and Wall to Stable Block SW of Chicheley Hall (Grade II) (1289599)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Wall with 3 Stone Piers SE of Chicheley Hall (Grade II) (1212330)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Binney, Marcus (2007). In Search of the Perfect House: 500 of the Best Buildings in Britain and Ireland. London, UK: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 9-780297-84455-6.

- Jenkins, Simon (2003). England's Thousand Best Houses. London, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-7139-9596-1.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Elizabeth (2003). Buckinghamshire. Buildings of England. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09584-8.

- Rees, Neil (2005). The Secret History of The Czech Connection – The Czechoslovak Government in Exile in London and Buckinghamshire. ISBN 978-0-9550883-0-8.

- Tipping, Henry Avray (1908). In English Homes: The Internal Character, Furniture & Adornments of Some of the Most Notable Houses of England. Vol. 2.